Introduction

Just because an area is “protected” does not necessarily mean it is free from tree loss. There are many ways to practice environmental conservation, and some methods are far more protective than others. In this analysis, I ask whether less protected parks in Malawi are subject to greater deforestation.

Analysis

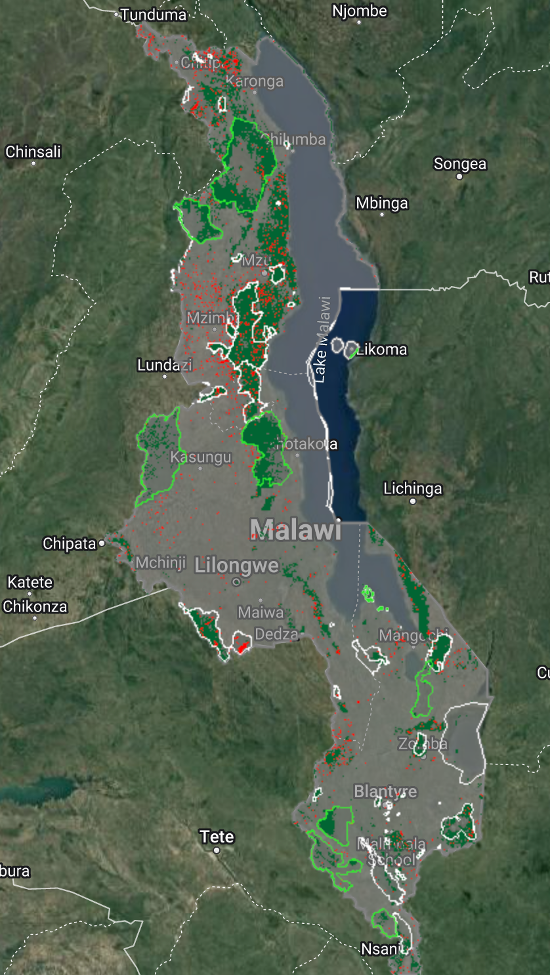

Using Google Earth Engine and Hansen’s Global Forest Change dataset, I find that in Malawi, less protected parks witness substantially higher levels of deforestation than strictly protected parks. In fact, the percentage of tree cover loss was 35 times greater in less protected parks, at 1.75% versus 0.05%. You can see these results clearly in figure 1 below. Areas outlined in neon green are strictly protected parks while areas outlined in white are less strictly protected parks. Red dots, which represent forest loss, are far more common inside of the white boundaries than the green boundaries.

In figure 1, tree cover is symbolized in dark green and tree loss in red, strictly protected areas are outlined in neon green, and less protected areas are outlined in white. Generated with Google Earth Engine. Please see my code here.

A Note on our Class Definitions

This analysis hinges on a few major assumptions. One relates to the way we classify strictly and less protected parks. In this project, we used the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) classifications of protected areas, assuming that the following categories are strictly protected:

- 1a – Strict Nature Preserve (0 in Malawi)

- 1b – Wilderness Area (0 in Malawi)

- II – National Park (5 in Malawi)

- III – Natural Monument or Feature (0 in Malawi)

- IV – Habitat/Species Management Area. (4 in Malawi)

We assumed that these categories are less protected:

- V – Protected Landscape/Seascape (0 in Malawi)

- VI – Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources (0 in Malawi)

- Not Reported (121 in Malawi)

- Not Applicable (3 in Malawi)

It seems reasonable to assume that Malawi’s National Parks and Habitat/Species Management Areas would be well protected, but we made a major assumption in our designation of the less protected parks. Of the 133 protected areas in Malawi, 121 of them do not have a reported IUCN category. We genuinely do not know the categorization of those parks, so we cannot deduce how well they are protected. Additionally, the IUCN categories are supposedly not applicable for 3 protected areas. With no additional information about these parks, it is difficult to assess the validity of our assumption that they are less protected. Because the IUCN categories of all of the ‘less protected’ parks were either not reported or not applicable, our designation of these parks as less protected is a substantial assumption that certainly impacted the results.

Discussion

The ways we define ‘forest’, ‘tree cover’, and ‘forest loss’ also affect our analysis. In this assignment, we considered a pixel to represent a ‘forest’ if it was composed at least 30% by tree cover. This may be a common threshold for this type of analysis, but it is also a subjective threshold. Personally, I understand the word ‘forest’ to mean a heavily wooded area, far more than 30% tree cover. The way we measure the percentage of tree cover and determine whether an area experienced forest loss is also subjective. For the purposes of this analysis, I used Hansen’s tree cover and forest loss bands. A more thorough investigation ought to interrogate the way Hansen et al calculated these bands and make any appropriate adjustments.

Furthermore, the methodology used in this analysis is incapable of telling when the loss of trees actually constitutes deforestation. For example, my analysis detected tree cover loss near Chikangawa, which falls within one of the less protected parks. Upon inspecting the area with Google Earth Pro, I found that there are regularly trees in this area. And when I researched the location, I discovered the presence of Kawandama Hills Plantation, which plants and harvests trees every year. Considering this region to be the subject of deforestation is misleading, because although trees are regularly lost in Chikangawa, they are also regularly replanted. This situation is not unique to Chikangawa and unquestionably affected the results of this analysis. Some locations, such as Nyika National Park, experienced loss of naturally occurring trees, while other locations, like Chongoni Forest, contain plantations. This analysis is a great first step towards identifying deforestation in Malawi but ought to be validated and supported with additional research.